Pinkhill Meadow – what are the ponds like after 30 years?

7th March 2017

We created the ponds on Pinkhill Meadow, with partners Thames Water and the Environment Agency, 30 years ago to restore this part of the River Thames floodplain. Now this is the best monitored pond complex in the UK and the ponds are some of Britain’s most diverse freshwater habitats.

Pinkhill Meadow ponds under construction in 1990/91, between the River Thames and Farmoor Reservoir (c) Environment Agency

Pinkhill Meadow ponds under construction in 1990/91, between the River Thames and Farmoor Reservoir (c) Environment Agency

In 1990, we started work on the creation of a new pond complex to try out many of the new ideas and concepts we’d been developing around designing and digging new ponds. Thanks to Thames Water and the Environment Agency, we had access to Pinkhill Meadow, a blank canvas nestling between Farmoor Reservoir and the River Thames in Oxfordshire, and funds to get the diggers in.

We designed the site and directed the excavation of 40 ponds in the meadow, along these principles:

- Creating a complex of pools of different sizes, depth, permanence and water source

- Ensuring that all water sources were unpolluted

- Creating broad wetland margins and long shallow drawdown zones at waterbody edges and on islands

- Undulating the drawdown to create hummocks and pools

Pinkhill Meadow in the early days (c) Environment Agency

Pinkhill Meadow in the early days (c) Environment Agency

These are now core tenets of our pond creation advice, but whilst we believed back then that it would bring about real benefits for wildlife, we didn’t yet have all the evidence. What we needed was data.

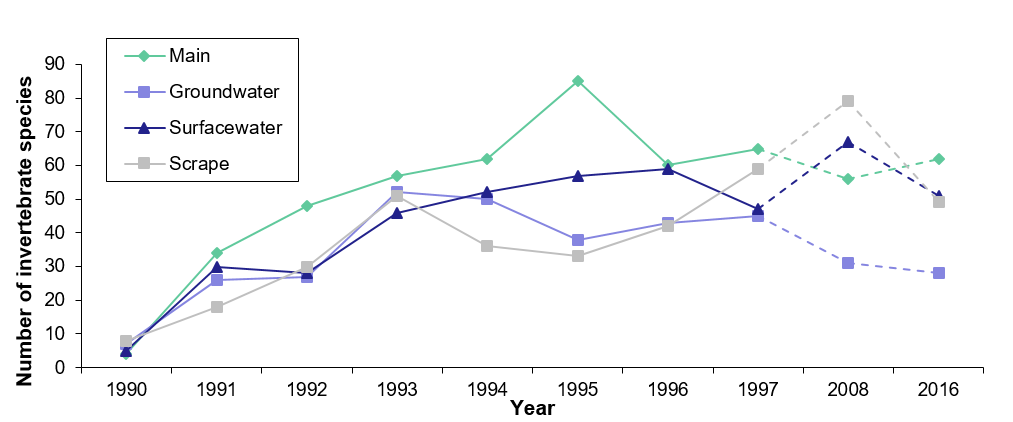

In 1991 we began a regular monitoring programme of the wetland plants and invertebrates on Pinkhill Meadow. We carried out detailed surveys of the four main ponds – Main Pond, Scrape, Surfacewater Pond, Groundwater Pond – and a search of the whole site.

In 1991 we began a regular monitoring programme of the wetland plants and invertebrates on Pinkhill Meadow. We carried out detailed surveys of the four main ponds – Main Pond, Scrape, Surfacewater Pond, Groundwater Pond – and a search of the whole site.

Here is a summary of what we have found over the last 26 years, including the most recent data collected in 2016, from Penny Williams, our Technical Director.

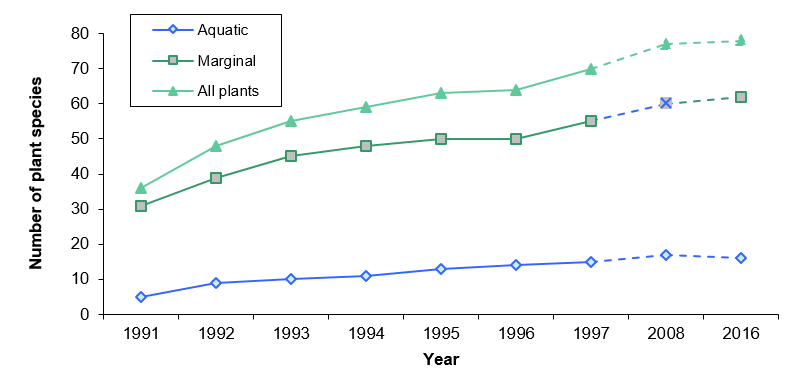

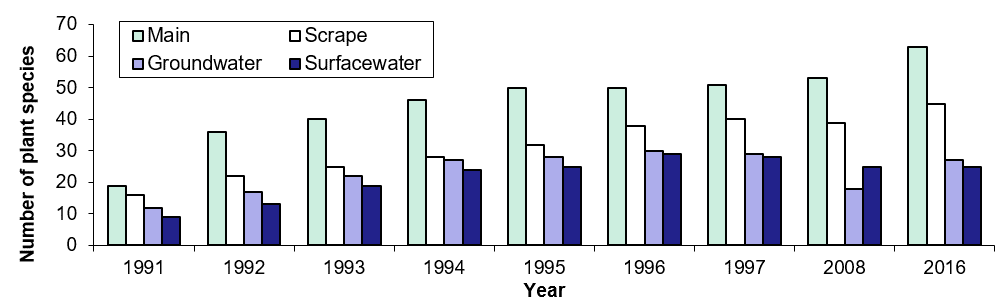

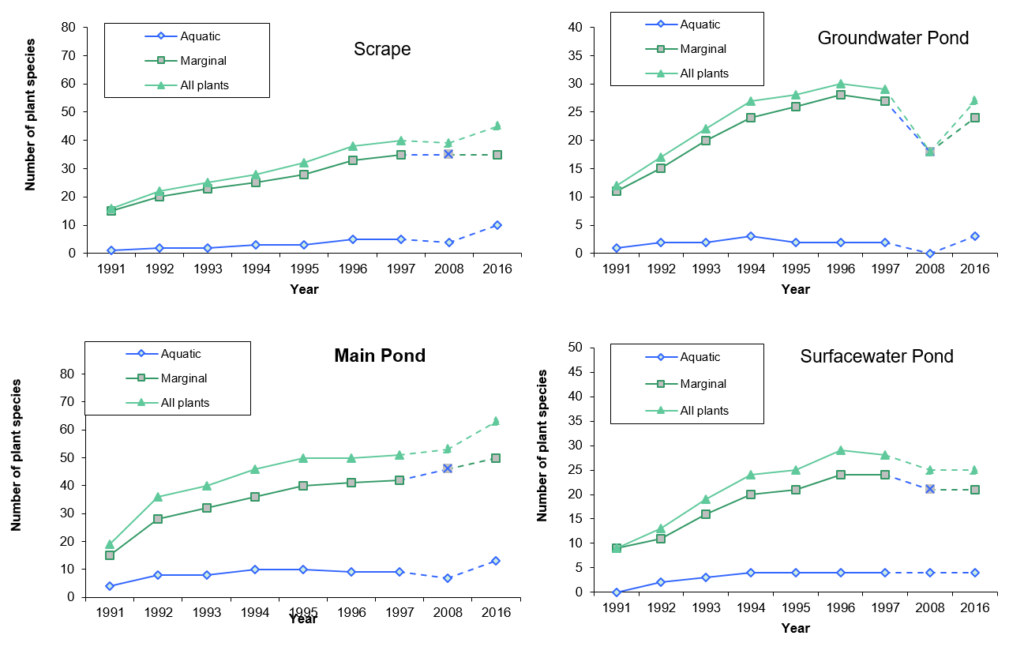

Wetland plants on Pinkhill Meadow

Pinkhill is exceptionally rich in wetland plants. It’s richness has only stabilised over the last eight years – plateauing at around 70 plant species.

The site colonised exceptionally well from the start, but a few things didn’t work out so well. A reedbed was planted (it was the only planting on site) at the edge of the site as a screen and to provide a different habitat, but the reeds encroached across the site. However, Pinkhill has, overall, maintained its richness even though many pools are heavily overgrown by Common Reed and becoming shaded by Willow and Alder.

The site was designed to be grazed, but it proved difficult to get grazing animals on site for many seasons. Unfortunately, this allowed tall sedges and rushes to fill in most of the subtle topography we’d created, and over the years the site began to scrub-up. We can only guess at what differences there might have been if grazing had been possible.

The Main Pond is still the richest waterbody on the site for plants, followed by the Scrape. The Surfacewater Pond and Groundwater Pond traditionally had similar plant richness. But in 2008 the Groundwater Pond declined in plant richness when swamped by reed. Surprisingly, richness increased again in 2016 as shade from developing willow suppressed the reed, allowing more marginal and submerged aquatics to thrive.

Looking at the details of the four ponds, we can see that most of the ponds have increased in plant richness since 2008. Increases in the number of marginal plants partly reflect the development of swamp habitat from the bank. In the Main Pond the islands have now been partly encroached by marginal emergent plants – leaving quiet backwater pools behind.

Looking at the details of the four ponds, we can see that most of the ponds have increased in plant richness since 2008. Increases in the number of marginal plants partly reflect the development of swamp habitat from the bank. In the Main Pond the islands have now been partly encroached by marginal emergent plants – leaving quiet backwater pools behind.

Uncommon plants on Pinkhill Meadow

Ragged Robin

Ragged Robin

The uncommon plants Rough Stonewort Chara aspera and Bristly Stonewort Chara hispida are both present on the site. As is Ragged Robin Silene flos-cuculi. This shouldn’t be a surprise, but this pretty flower has declined so much it is now on the England Red List, classified as Near Threatened!

Marsh Dock Rumex palustris is another nice record as it is very uncommon in Oxfordshire, bordering Near Threatened. It has experienced a 33% decline in recent years.

Plants we’re happy to lose

There are a couple of plants we are happy to say farewell to. We have ‘lost’ two non-native plants species that were accidentally introduced to the site when the reeds were planted up: Monkeyflower Mimulus sp. and Crassula helmsii . There were extensive stands of Crassula in a reed bed. Two herbicide treatments in the 1990s only knocked it back, but black plastic sheeting and natural shade from the reeds have (we hope) eradicated it over the last couple of years.

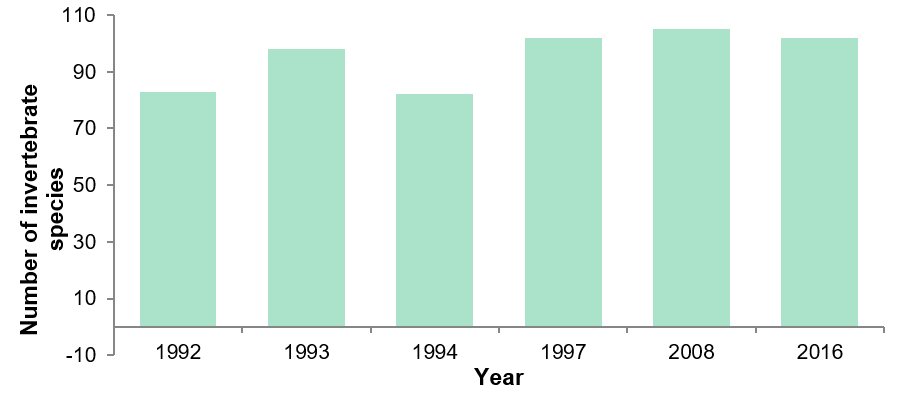

Aquatic invertebrates on Pinkhill Meadow

As the chart above shows, site richness – the total number of aquatic invertebrate species – started off quite high, and has plateaued at just over 100 species. This is a very rich invertebrate assemblage, and includes a few uncommon water beetles, but no extremely rare species.

It’s nice to see there are Swan Mussels in the main pond, new dragonfly species are breeding including the Hairy Dragonfly Brachytron pratense which is uncommon though increasing in the UK, and the site is still being colonised by water snails – the slow movers!

All ponds are still very rich in species, even though we have seen a decline in three of the four monitored ponds. The loss is mainly of water beetle species which suggests a decline in edge habitat structure, a loss of complexity. This is probably due to the dominance by tall emergent plants which form a very simple underwater structure.

In the last eight years, the Main Pond has had a slight increase in species richness, probably because of the backwater pools that have formed behind the islands.

How’s Pinkhill Meadow doing overall?

The site is maintaining an exceptional richness despite the scrub and reeds. This is likely a testament to the wide range of habitats on the site, and the decent water quality.

Pinkhill Meadow in the early days (c) Environment Agency

Pinkhill Meadow in the early days (c) Environment Agency

To put it into context, an individual pond with 30 or more wetland plants species or 50 or more aquatic macro-invertebrate species qualifies as a Priority Pond, and should be given priority for protection for their wildlife interest. The richest pond we’ve ever found is Castor Hanglands in Cambridgeshire, where we found 136 invertebrate species.

A some point, each of the four ponds surveyed in detail have met one of these criteria.

Pinkhill Meadow is recognised as a Flagship Pond site, because of the richness of the ponds, the unique history and detailed monitoring of the site.

What next?

Thanks to funding from TOE2, the Heritage Lottery Fund, and site owners Thames Water, we are very excited about the next chapter of Pinkhill Meadow’s story.

Volunteers have been busy clearing scrub. This work has made it possible for a digger to get into parts of the site to carry out some dredging, clear some vegetation, and create new pools.

Volunteers have been busy clearing scrub. This work has made it possible for a digger to get into parts of the site to carry out some dredging, clear some vegetation, and create new pools.

New fencing means the site is ready for grazing, and we now await the arrival of a herd of Dexter cattle that will graze the site in autumn and winter. Grazing and poaching by the cattle will really improve the edge structure of the ponds.

We are really excited to see how Pinkhill Meadow develops in the future.

Find out more

- Learn more about the Flagship Ponds project and the work we are doing to protect our most important ponds and their wildlife.

- Read a detailed account of the creation of Pinkhill Meadow in the River Restoration Centre’s Manual of River Restoration Techniques (note the contact details on this doc are out of date).

- Use the Pond Creation Toolkit to plan and carry out your own top quality pond creation scheme.

- See our tips on making a great garden pond for wildlife.

- Find out about the professional services we offer.