Glutinous Snail: a species on the cusp of extinction

17th August 2022

Conservationist Ian Hughes urges us not to give up on the Glutinous Snail, a critically endangered species now reduced to a single population in a Welsh lake.

The Glutinous Snail is extinct in England and, in Britain, is now found in just one lake: Llyn Tegid in North Wales. This distinctive creature could be on the brink of extinction, but let’s not lose hope of saving Britain’s rarest water snail.

An unusual looking mollusc

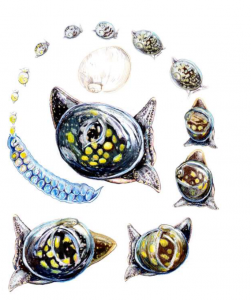

The Glutinous Snail (Myxas glutinosa) is a small and very unusual looking mollusc. On first sight, it resembles a tiny dark blob of goo. This goo is, in fact, a unique feature that isn’t found in any other freshwater snail. It’s covered by a ‘glutinous’ mantle: a layer of translucent tissue that wraps around the shell from beneath, sealing at the top of the shell like a purse. Because it helps to compensate for the very thin transparent shell, the glutinous mantle could be an adaptation to a habitat with poor calcium levels.

The Glutinous Snail has complete muscular control of this glutinous mantle and can expose the shell or enclose it completely at will. Beneath the goo, its shell looks quite like that of the Wandering Snail (Ampullaceana balthica) – one of the most common and ubiquitous of all the freshwater snails.

The mantle and body are speckled with freckle-like gold spots. The shell is largely dark brown but with gold-coloured blotches and spots, which shine through the glutinous mantle. Unlike garden snails, its eyes are at the base of the tentacles, which look like large pointed ears.

At under 1.5 cm in length, the Glutinous Snail is less than half the size of the familiar Great Pond Snail that many people will see in their garden ponds. Its shape is very distinctive: look closely, and you realise that it has the most ‘ear-shaped’ shell of all the freshwater snails. The last whorl of the shell creates a large cavity for the body, with a tiny, almost invisible spire at the top. Its shell is also very thin, transparent and fragile, making these creatures almost impossible to handle.

The decline of the Glutinous Snail

The Glutinous Snail is often described as Britain’s rarest snail and, sadly, it is also one of the most threatened freshwater molluscs in Europe. Historically, it has been found in a wide variety of environments, from the Alps to the Arctic. However, where up-to-date evidence exists, it is recorded as isolated or declining (or both) and is thought to now be extinct in Austria, Germany and England.

In Britain, the Glutinous Snail is now restricted to a single water body – Llyn Tegid in north Wales. The only other known population in the British Isles is in canals in Ireland, but its status there is unclear and was last reported as declining. The species was rediscovered by Martin Willing and David Holyoak at Llyn Tegid in 1998. Since then, the population has been monitored with funding from Natural Resources Wales, by taking counts at set monitoring stations since 2000.

Previously found in Kent, Surrey, East Anglia, the Thames Valley, Lincolnshire and Cumbria, the species suffered a sharp decline in the 20th century. The most recent English record for the Glutinous Snail is from Kennington Pit, a pond on the edge of Oxford, where it was first spotted in 1988 and last seen in 1993.

So, why has the Glutinous Snail suffered such a sudden and serious decline?

The Glutinous Snail is highly sensitive to deterioration in water quality. It is thought that this species could be more sensitive than other snails because its glutinous mantle allows greater absorption. The most widely-accepted cause for its decline is the increase in pollutants, from farming and industry, entering ponds, ditches, lakes and streams.

We also know that it is sensitive to handling and disturbance so this may have contributed to its disappearance from some small water bodies. Other theories include the species’ limited diet, which makes it vulnerable when plant biodiversity changes.

Llyn Tegid: Britain’s last stronghold for the Glutinous Snail

Identified by Freshwater Habitats Trust as a Flagship Freshwater Site, Llyn Tegid is now the only place in Britain that is known to be inhabited by the Glutinous Snail. At 3.7 miles long and 0.5 miles wide, Llyn Tegid is the largest natural lake in Wales.

Why is this glacial lake, on the edge of the Snowdonia National Park, the last stronghold in Britain for the Glutinous Snail?

Llyn Tegid is a place of exceptional importance for freshwater wildlife and is one of our finest freshwater habitats. This is largely thanks to it being an upland lake, which receives water from unpolluted sources, in an area with a low human population. A Ramsar wetland site of importance, it is also home to a unique native fish: the Gwyniad.

But there could be another reason why this single lake is the Glutinous Snail’s last British stronghold.

The Glutinous Snail is quite choosy about its food, limiting itself mainly to algae, which it rasps from the water surface. Unlike the Slender Pond Snail, the Glutinous Snail cannot make itself dormant when food is short. This suggests that it may need an environment that supplies readily rasp-able algae. With constantly changing water levels, the wave action at Llyn Tegid creates a shoreline of stones coated only in thin algal mats – perfect for the Glutinous Snail.

The Glutinous Snail is sometimes said to favour stony substrates with very little vegetation. However, the best known site at Llyn Tegid is a sheltered bay with a silty substrate and comparatively rich plant growth and water-logged wood. While it is generally known to be a solitary animal, here the Glutinous Snail is found in twos and threes. We still have much to learn about what this species needs to survive but, for now, it seems to have found conditions which it likes in this particular lake.

Can we save the Glutinous Snail?

Its sensitivity to pollution, limited diet, fragility and seemingly limited opportunities for dispersal makes this species highly vulnerable. Sadly, isolated ponds, canals or rivers are unlikely to be re-populated naturally. This makes the future look rather bleak for the Glutinous Snail.

However, in 2017, with support from Freshwater Habitats Trust, I set about establishing an ex-situ colony of Glutinous Snails, starting out with just 10 individuals. The ponds are now home to a thriving breeding population. We hope that one day we will be able to introduce snails from this colony to wild habitats. However, we have not yet been able to find suitable locations that meet the strict legislation that’s in place for the species.

Perhaps the most important thing we can all do to provide a future for the Glutinous Snail is to fight for the regeneration of our freshwaters. Many water bodies have degraded irrevocably, so it’s critically important that the remaining high quality habitats are protected and well managed. Water bodies like Llyn Tegid represent some of the least impacted, most diverse freshwater habitats in the UK. Let’s try and keep them that way – for the Glutinous Snail and all freshwater wildlife.

Ian Hughes is an artist and conservationist based in Ceredigion. His family business, Lifeforms Art creates beautiful products for fellow nature lovers, such as this dragonfly range for Freshwater Habitats Trust.

To protect freshwater wildlife, including endangered species like the Glutinous Snail, support our work by making a donation or becoming a volunteer.