Celebrating freshwater wildlife for 30 years

14th February 2018

It’s a special year for us…

Back in the mid-eighties Jeremy Biggs joined an environmental consultancy in Oxford, run by Anne Powell and Roger Sweeting. Together they dreamed of doing something for nature conservation, and began to cast their net over the freshwater world to look for likely candidates.

Ponds were an obvious starting place – it seemed that freshwater biologists often began their careers by peering into these little waterbodies, but then deserted them for more apparently important habitats like rivers and lakes. As a result, knowledge about the ecology of ponds was at least 50 years out of date.

On the 1st January 1988, with the start of the Oxfordshire Pond Survey, the Freshwater Habitats Trust was born – then known as ‘Pond Action’. Thirty years later, the organisation is still going strong – as the only UK research and conservation charity dedicated to the protection of our most endangered freshwater habitats and species.

The thirty-year period has seen many changes to our understanding of how to conserve freshwater biodiversity – who, for one, would have guessed how important little ponds would turn out to be? Here’s a high-velocity tour through some of the Trust’s contributions…

At the start of the 1990s, the Trust’s first major initiative was the National Pond Survey which looked at Britain’s best ponds in some wonderful places – everywhere from the heathland pools of Bodmin Moor in Cornwall to wild lochans in Abernethy Forest in the Cairngorms. The survey still forms the benchmark for high quality ponds, against which other ponds can be compared. In the Lowland Pond Survey and the 2007 Countryside Survey – at roughly 10 year intervals – it forms the reference condition used to judge the true state of ponds in the wider countryside.

The Cole paper highlighted the contribution that ponds made to biodiversity in an area

The Cole paper highlighted the contribution that ponds made to biodiversity in an area

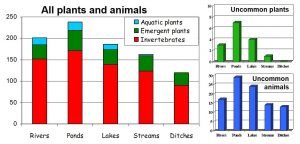

The National Pond survey showed that ponds had an unexpectedly high conservation value – but in practice this didn’t make much of a splash in the freshwater world. The thing that really changed views was a late 90’s study that compared ponds with rivers and lakes – habitats that were already valued. It is extraordinary to think that, even by the 1990s no-one had ever compared the biodiversity value of different waterbody types. Biologists worked in silos – usually you were either a river ecologist or a lake ecologist. The Trust’s survey of all waterbodies across the catchment of the River Cole on Oxfordshire’s border produced a landmark paper, now with well over 600 citations, which clearly showed that, at landscape scale, ponds were the most biodiverse habitat type. Published in 2003, it was a finding that came just in time to ensure that ponds received Priority Habitat status. It also highlighted a way we could all help boost freshwater wildlife in an area: creating ponds.

The making of Pinkhill Meadow, between Farmoor Reservoir and the River Thames (c) Alistair Driver/Environment Agency

The making of Pinkhill Meadow, between Farmoor Reservoir and the River Thames (c) Alistair Driver/Environment Agency

The Trust’s first go at putting its new knowledge into practice began in the early 1990s with a pond creation project in a 5 ha field owned by Thames Water, sandwiched between Farmoor Reservoir and the River Thames. Thanks to colleagues at the Environment Agency, the Trust was able to design a mosaic of ponds with clean water, different depths and permanence, and wide drawdown zones. Pinkhill Meadow is now a nationally important Flagship Pond site and the best monitored pond site in the country. This Oxfordshire site was also the inspiration for many thousands of new ponds that have been created across the UK as part of the Trust’s ongoing Million Ponds Project: helping anyone to bring wonderful clean water habitats back into our countryside with the help of the Pond Creation Toolkit.

Over the last decade, the Freshwater Habitat Trust has continued to work with many partners to study, create and manage ponds across the UK. Recent initiatives include PondNet, a national pond surveillance programme to keep an eye on changes in pond quality and the status of rare plants and animals, and Flagship Ponds, working with communities to ensure that our best ponds and the rare wildlife they are home to, have a secure future.

Increasingly the Trust’s focus has also widened – now the Trust spends almost as much time working with streams, ditches and rivers as ponds. There’s still no lack of challenges however. Indeed, after thirty years of passionate study and advocacy, the Trust is looking forward to setting a course for the next thirty years.